Torque Control Short Story Club: "No Time Like the Present"

An open discussion by a wide variety of readers and writers of Carol Emshwiller's recent story "No Time Like the Present" from Lightspeed Magazine.

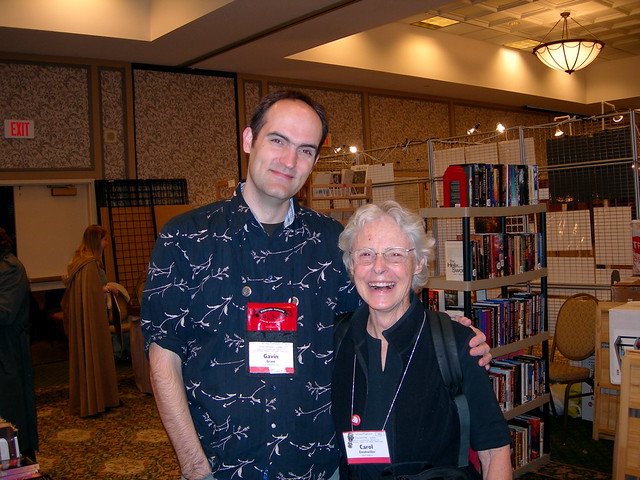

Gavin Grant: Notes Toward an Article on Carol Emshwiller

|

| Gavin Grant & Carol Emshwiller |

If someone were to compile one of those futile lists of the top hundred writers in the world right Now! I’d have to hack into the results and replace the name of one of the politely-angry young men in the top ten with Carol Emshwiller’s. I wouldn’t put her in the top five, but only to avert the pollsters suspicions. Number six then, or number seven.

I imagine that when they discovered I’d spoofed their poll, said pollsters might be ticked off. But if they attempted to track me down, I expect there would be a Spartacus moment (perhaps without all the cleft chins) as writers from all around the world would stepped themselves forward to say, “I put Carol Emshwiller in the top ten,” or, “It was I who fixed your silly poll,” and so on.

Carol Emshwiller’s writing, and she herself, inspires that kind of action.

CONTINUE READING

Carmen Dog: A Review by Nymeth

Carol Emshwiller is very funny – funny in a straight-faced, ironic way that reminded me a little of Margaret Atwood. And being funny, of course, doesn’t mean that this isn’t a serious book with very frightening implications. The fact that it’s a humorous fantasy might make it possible for us to distance ourselves from what’s happening in a way that a more realistic story about cruelty, discrimination, powerlessness and subjugation wouldn’t allow. But then again, it also allows Carol Emshwiller to take it to places where a realistic story wouldn’t go—and this is why I love fantasy. The harshness is there all the same, and there are things to be learned from this distance. If you look beyond the surface, it's really as disturbing as The Handmaid's Tale.

CONTINUE READING

Justine Larbalestier on Emshwiller & Le Guin (2003)

Saturday’s conversation between Carol Emshwiller and Ursula Le Guin was fabulous and moving and for me the highlight of the 2003 WisCon. Eileen Gunn fed them the occasional question, but mostly they chatted amongst themselves, covering writing about the recent war (Ursula needs to stew on things for a while, so hasn’t yet; for Carol the process is more immediate—she’s already sold a number of stories on the subject, at least one of which is in print), teaching the craft of writing (Ursula loves to steer her students towards contemplating the fine art of comma placement), raising childen while trying to write (apparently the trick is to get them to go to bed by 7:30pm) and a great deal more about the road they’ve had to hoe as writers. It was glorious wittnessing such a warm and easy friendship between two very different women. Ursula’s path has been for the most part golden (does anyone truly have an easy path?) with supportive parents and spouse, while Carol came to writing later, with little support and a certain amount of hinderance from her spouse. Her discussion of the difficulties of stealing time to write whle raising her children ("I felt like I couldn’t breathe," she said at one point, smiling) elicited hisses for her late husband from the audience, and yet there was no condemnation in her words nor even the faintest whiff of bitterness. Ursula claimed to be a rabbit in comparison to Carol’s bravery. Carol claimed that she too was a rabbit. John Kessel dryly pointed out from the audience that, if so, she was a very brave rabbit. The audience laughed a great deal, and I know that I was not the only one whose eyes filled with tears.

CONTINUE READING

CONTINUE READING

Carol Emshwiller: An Appreciation by L. Timmel Duchamp (2003)

This essay first appeared in the WisCon 27 Souvenir Book.

Souvenir-Book appreciations are typically written by friends and long-time associates of a con’s Guests of Honor and usually focus on the GoH’s personal and professional biography. Since I have had the pleasure of meeting Carol Emswhiller personally only once, I will focus instead on my many years’ relationship with a single aspect of the person who is Carol Emshwiller, viz., that mysterious presence readers sense lurking within or perhaps behind the texts of her stories and novels, a presence generally known as the "author." This relationship between a single reader and the particular presence of an author, although seemingly abstract and impersonal, is in practice a deeply intimate one. It is also an extremely privileged relationship, since only a relatively few authors’ texts create a sense of that mysterious, very particular presence with which readers so delight in engaging. I recognized and engaged with that presence the first time I read a Carol Emswhiller story, a presence that so intrigued and teased and dialogued with me that the author went at once onto what I call my "magic" list of must-buy authors whose work I’m always on the lookout for.

CONTINUE READING

Souvenir-Book appreciations are typically written by friends and long-time associates of a con’s Guests of Honor and usually focus on the GoH’s personal and professional biography. Since I have had the pleasure of meeting Carol Emswhiller personally only once, I will focus instead on my many years’ relationship with a single aspect of the person who is Carol Emshwiller, viz., that mysterious presence readers sense lurking within or perhaps behind the texts of her stories and novels, a presence generally known as the "author." This relationship between a single reader and the particular presence of an author, although seemingly abstract and impersonal, is in practice a deeply intimate one. It is also an extremely privileged relationship, since only a relatively few authors’ texts create a sense of that mysterious, very particular presence with which readers so delight in engaging. I recognized and engaged with that presence the first time I read a Carol Emswhiller story, a presence that so intrigued and teased and dialogued with me that the author went at once onto what I call my "magic" list of must-buy authors whose work I’m always on the lookout for.

CONTINUE READING

Carol Emshwiller Interviewed by Patrick Weekes (2001)

The first thing that Carol Emshwiller said to us when she began teaching in the final week of the 2000 Clarion West Writers Workshop was, "Practice doesn't make perfect. Practice makes permanent." This was the first clue I had to the importance Carol places on precision and refinement. Her award-winning novels and short story collections have been lauded as both experimental and focused, free-flowing but carefully plotted. Her latest novel, Leaping Man Hill, came out in 1999, and is a sequel to Ledoyt, which came out in 1995.

Carol also spends a good deal of her time teaching. Students of the courses she teaches at New York University or the Clarion workshops have been impressed by her keen eye, her self-deprecating wit, and her deep and subtle understanding of human nature -- characteristics that have also come through in her writing. She lives in New York in the winter and California in the summer.

Patrick Weekes: First and foremost, could you tell us about yourself, anything that I didn't mention?

Carol Emshwiller: Whew, that first question seems hard. I know I shouldn't say anything that was already in the SFWA home page. Hmmm. I have three brothers and that has had a big (!) influence on my life. I always thought of myself as one of the boys, though a defective one.

PW: What was it that finally made you start writing? You said that you didn't start until after your first child was born, and you mentioned on the SFWA web page that you'd always hated writing.

CE: It was the science fiction people that Ed got to know when he started illustrating. They talked about writing as though somebody who wasn't particularly talented could actually do it. There were rules and techniques and you didn't have to be a genius and maybe even sell to SF mags. Just tell a story. I liked the SF world that Ed began to be in and I wanted to be in it, too. That's how I started.

CONTINUE READING

Carol also spends a good deal of her time teaching. Students of the courses she teaches at New York University or the Clarion workshops have been impressed by her keen eye, her self-deprecating wit, and her deep and subtle understanding of human nature -- characteristics that have also come through in her writing. She lives in New York in the winter and California in the summer.

Patrick Weekes: First and foremost, could you tell us about yourself, anything that I didn't mention?

Carol Emshwiller: Whew, that first question seems hard. I know I shouldn't say anything that was already in the SFWA home page. Hmmm. I have three brothers and that has had a big (!) influence on my life. I always thought of myself as one of the boys, though a defective one.

PW: What was it that finally made you start writing? You said that you didn't start until after your first child was born, and you mentioned on the SFWA web page that you'd always hated writing.

CE: It was the science fiction people that Ed got to know when he started illustrating. They talked about writing as though somebody who wasn't particularly talented could actually do it. There were rules and techniques and you didn't have to be a genius and maybe even sell to SF mags. Just tell a story. I liked the SF world that Ed began to be in and I wanted to be in it, too. That's how I started.

CONTINUE READING

Carol Emshwiller Interviewed by Robert Freeman Wexler (2002)

Robert Freeman Wexler: The Mount is more explicitly science fiction than much of your work. It’s an alien invasion story, though you deal more with relationships than battles. Not at all like the way Hollywood portrays anything with aliens. I’m wondering how the novel took shape. For example, did you have the idea of these aliens using people as horses, and work out some of the historical details later, such as how the situation started, how the aliens got there, etc.?

Carol Emshwiller: I had just taken a class in the psychology of prey animals vs. predators.

It was supposed to be about the psychology of horses, but it contrasted all prey with all kinds of predators—about how we are predators riding a prey. I think the first thing I wanted to do with The Mount was to reverse that—to put a prey animal riding a predator. And I thought how interesting it would be if the prey animal had all the acute senses that we don’t have. Then I started, right in the middle, with the first chapter which is in the point of view of one of the hoots. In the beginning I thought it was a short story, but I got so interested (in chapter 2) in Charley’s desire to be a good slave that it just went on. I fell in love with Little Master as much as I fell in love with Charley.

I actually wanted the reader to feel torn about what was best, being looked after or having the hardships of being “free.” I thought, just because I like camping out and hardships and getting along with less, doesn’t mean that everybody would like it or is suited to that life. I still don’t know for sure what I think about that. It’s such a cliché to say and so easy to say, “Of course freedom is best.” Maybe eating regularly and staying warm is just as good.

Interview: Carol Emshwiller on "The Abominable Child's Tale" (2010)

Charles Tan: Hi! Thanks for agreeing to do the interview. What's is it about "fuzzy people" that interests you? What made you decide to finally use Big Foot?

Carol Emshwiller: Fuzzy people? and why big foot? Those questions go together for me. I don't think I have any special feelings for "fuzzy" people, but I do have for big foot and have for a long time. I love the idea of people who have avoided us all this time and who live in the mountains. They're smart and wild at the same time. I want them to be beautiful, too. I liked using teenagers in my story because they're more reckless, they try all sorts of things, and they have an innocence and acceptance of things (OK, so you're a big foot), that I wanted to use in the story.

CONTINUE READING

Carol Emshwiller: Fuzzy people? and why big foot? Those questions go together for me. I don't think I have any special feelings for "fuzzy" people, but I do have for big foot and have for a long time. I love the idea of people who have avoided us all this time and who live in the mountains. They're smart and wild at the same time. I want them to be beautiful, too. I liked using teenagers in my story because they're more reckless, they try all sorts of things, and they have an innocence and acceptance of things (OK, so you're a big foot), that I wanted to use in the story.

CONTINUE READING

Matthew Cheney on Mister Boots

Get yourself to the children's aisle, because Mister Boots is one of Carol Emshwiller's most satisfying books, which is to say it is a novel of skill and beauty and sadness and love, which is to say it is the sort of book that brings depth to our lives. It is being marketed as something for kids, and that is a good thing, because kids need this book, but so do those of us who are busily trying to digest our inner children into post-industrial waste.

The title character is a man who is also a horse. He escapes from his fellow horses and is found, naked and human, by the novel's narrator, a ten-year-old girl named Bobby who lives as a boy. Bobby's father was a stage magician who took his frustrations out on the backs of his wife and children with a whip, but who ran away from the family after growing horrified at all he had done. He returns when Bobby's mother dies, shortly after Mister Boots and Bobby's older sister Jocelyn have fallen in love, and they all head off for adventures on the road, until the dust storms of unfettered capitalism blow into the Great Depression, and the stage magician can't make his angers disappear.

The plot's rivets make the book a quick read, but the themes beneath the actions transform it into art.

CONTINUE READING

L. Timmel Duchamp on 2 Early Stories by Carol Emshwiller

When I saw Carol Emshwiller's Joy in Our Cause in the dealer's room at WisCon 25, I took no notice of its 1974 publication date. My tastes in reading might shift over the years, and certainly writers' styles do as well, but already familiar with early Emshwiller, I did not doubt that I would be in every way delighted with the collection. And indeed when I at last sat down to read it, my pleasure exceeded expectations. Interestingly, however, I found my enjoyment mediated by my awareness of the stories' (and the collection's) historical context. The historical context in this case included my personal as well as intellectual history. In story after story I picked up cultural resonances that I had not realized were still accessible to me. Repeatedly I wished I had known of Carol Emshwiller's existence in the late '60s and early '70s when, struggling to compose music while being told that women could only be mediocre and derivative creators, I was starved for the experimental work of other women.

Most surprising was my realization that I had undergone a significant shift in the way in which I constructed gender in the 1970s from the way in which I do now. Although I have changed greatly as an individual, it is more to the point that the gendering of narrative conventions that govern how we read has changed, also. The difference in our ideas, for instance, of what is plausible behavior or affect in female characters in some cases renders us unable to read the same story we read in years past. It is this particular difference in context that I would like to consider in reading "Sex and/or Mr. Morrison."

CONTINUE READING

Most surprising was my realization that I had undergone a significant shift in the way in which I constructed gender in the 1970s from the way in which I do now. Although I have changed greatly as an individual, it is more to the point that the gendering of narrative conventions that govern how we read has changed, also. The difference in our ideas, for instance, of what is plausible behavior or affect in female characters in some cases renders us unable to read the same story we read in years past. It is this particular difference in context that I would like to consider in reading "Sex and/or Mr. Morrison."

CONTINUE READING

"No Time Like the Present" by Carol Emshwiller

A lot of new rich people have moved into the best houses in town—those big ones up on the hill that overlook the lake. What with the depression, some of those houses have been on the market for a long time. They’d gotten pretty run down, but the new people all seem to have plenty of money and fixed them up right away. Added docks and decks and tall fences. It was our fathers, mine included, who did all the work for them. I asked my dad what their houses were like and he said, “Just like ours only richer.”

As far as we know, none of those people have jobs. It’s as if all the families are independently wealthy.

Those people look like us only not exactly. They’re taller and skinnier and they’re all blonds. They don’t talk like us either. English does seem to be their native language, but it’s an odd English. Their kids keep saying, “Shoe dad,” and, “Bite the boot.” They shout to each other to, “Evolve!”

CONTINUE READING AT LIGHTSPEED MAGAZINE...

As far as we know, none of those people have jobs. It’s as if all the families are independently wealthy.

Those people look like us only not exactly. They’re taller and skinnier and they’re all blonds. They don’t talk like us either. English does seem to be their native language, but it’s an odd English. Their kids keep saying, “Shoe dad,” and, “Bite the boot.” They shout to each other to, “Evolve!”

CONTINUE READING AT LIGHTSPEED MAGAZINE...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)